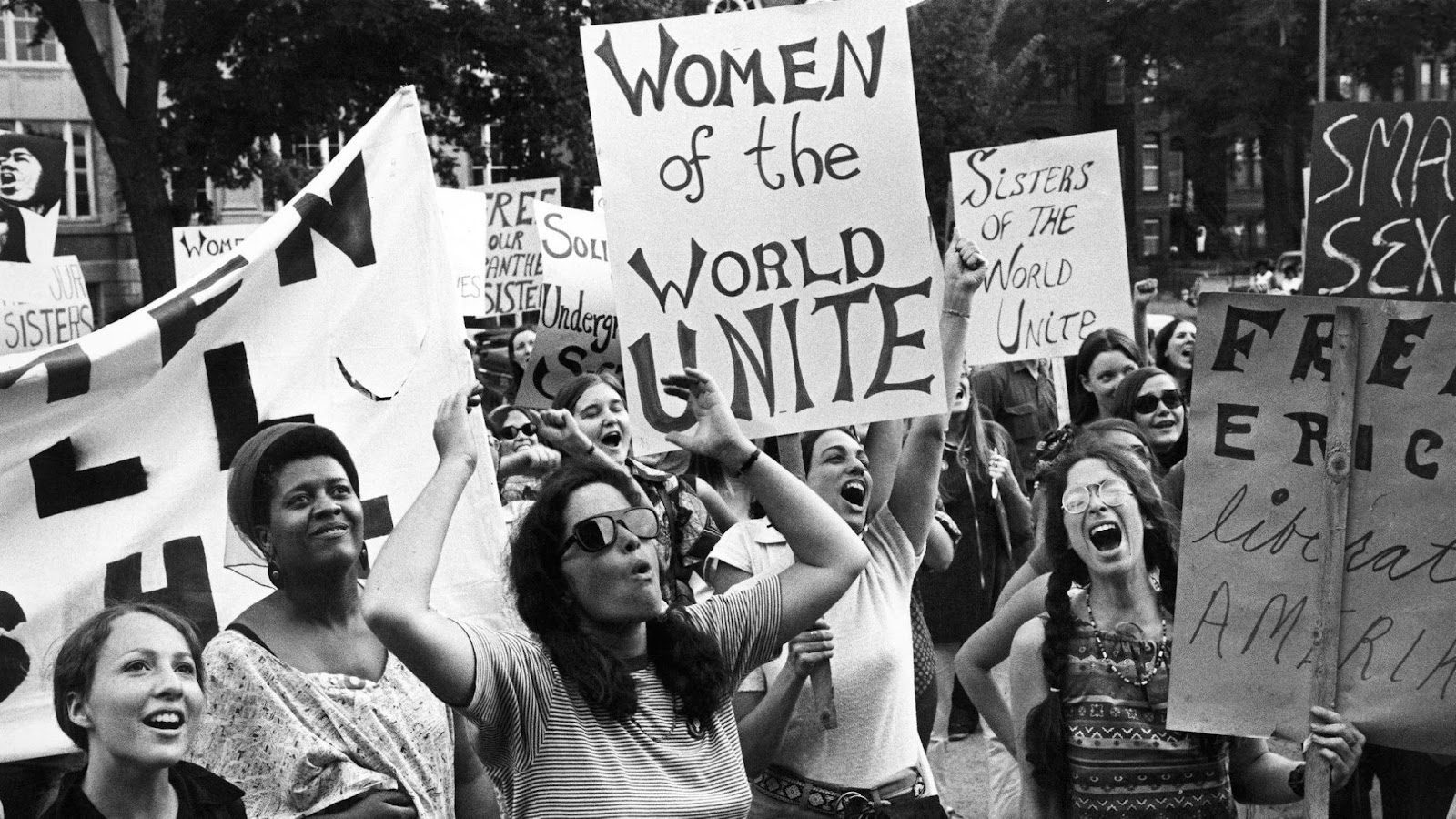

The word “feminism” first appeared in French and Dutch in 1872. Later it spread around the world, particularly in America. At different times and under the influence of various circumstances, the reasons for feminist activism varied among feminists. Some fought for women’s right to vote, others for the right to study and work with equal pay to men and others for sexual freedom.

In the 21st century, when in most countries the rights of women and men are equal, feminists are engaged in a more in-depth exploration of the formation of women’s issues in the world. Susan Gubar is one of them. Read more on brooklynka.com.

Woman-centeredness

Susan Gubar was born in Brooklyn in 1944. The childhood of the future fighter for feminist ideas had a typical childhood—school, friends, childhood hobbies. In her youth, Susan was a dedicated learner. She graduated from the City University of New York in 1965. Later, in 1970, the Feminist Press appeared at the same university, an independent publication that published materials on social and gender justice issues. It was created as a counterweight to all the literary clichés and stereotypes about women. Unfortunately, it was after Susan had graduated from college.

She chose English literature as her main subject of study at the university. Her studies did not stop there. Susan Gubar had a master’s degree from the University of Michigan and a doctorate from the University of Iowa. After such a long study, Susan went to teach. The central theme of not only her work but also her life was the place of women in this world. At Indiana University, she taught English and women’s studies. Through the lens of literature and women in it, she tried to understand this world. She had a special approach to analyzing literature through the foundations of feminism.

The formation of her worldview and, in general, the formation of an analysis of works focused exclusively on women and their role, was influenced by many feminist scholars. Key figures among them include Sandra Gilbert, Adrienne Rich, Elaine Showalter, Kate Millett and Luce Irigaray.

The very essence of the concept of “woman-centeredness” implies taking into account the achievements of women. In world literature, there are dozens of confirmations of classic and popular works where everything done by a woman is devalued. Her role is reduced to some biological characteristics and nothing more. It’s the same in the real world, especially in the realm of science. There are fewer women’s achievements not because they are not as intelligent but rather because they are not taken seriously and underestimated.

Since Susan Gubar was a professor of English literature, she explored the problem of “woman-centeredness” primarily through literature. She tried to find manifestations of the female voice in literature and the events described. Through the literary world, she understood who women were in a particular era and how society treated them, as well as the roles society assigned to them.

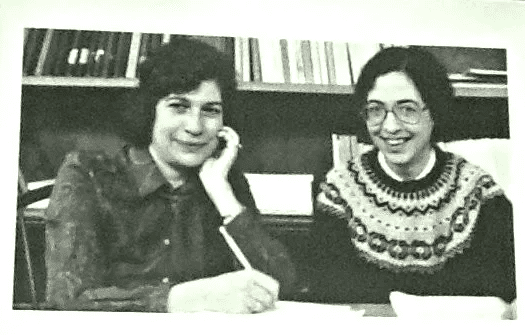

Gubar and Gilbert

In the early 1970s, Susan Gubar and Sandra Gilbert worked together at Indiana University. There they taught a course on women’s literature. Immersing themselves in this topic, they co-authored a work that made them famous in the world of feminist literature and the study of the role of women, The Madwoman in the Attic. In the 21st century, this work would be classified as nonfiction, a genre that is becoming increasingly popular. But even then, it was duly appreciated. The work was nominated for the National Book Critics Circle Award and the Pulitzer Prize.

In their scientific work, Gubar and Gilbert referred to the analysis of works by Mary Shelley, Jane Austen, the Brontë sisters, Emily Dickinson, and other British and American female writers of the 19th century. When the friends began their analysis, they had a completely different goal. They wanted to identify the aesthetic component of women’s literature but unexpectedly stumbled upon something else entirely, namely the unstable position of women writers in the world. It would seem that the world of literature doesn’t have the same rigid superstitions and boundaries as the world of science, but even there, the works of women were not taken as seriously, even in the genre of drama.

While studying the works of male authors whose works featured female characters, they were presented in a distorted way or muted altogether for the benefit of the male image. In other words, their role in depicting the world and their achievements were belittled. This permeated the substance of literature to such an extent that even 19th-century female authors fell into the same trap. They followed the model of the female image already created by men.

No Man’s Land

No Man’s Land is a three-volume sequel to The Madwoman in the Attic. In their new work, Gubar and Gilbert evaluated the struggle between the two sexes from a feminist perspective. They examined literary works that contrasted the two sexes and tried to look at them from a different angle. To achieve more accurate and multifaceted results, they considered the works of both male and female writers.

In addition to writing her own works, Gubar also co-edited the Norton Anthology of Literature by Women. Together with like-minded people, including Gilbert, they compiled all literary works authored by women into one book. Their selection included the most significant works in their opinion. In the second and third editions, the same idea is revealed from the perspective of women’s racial, religious, social, cultural and socioeconomic backgrounds.

Gubar and Gilbert included authors from the Middle Ages, the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, as well as the literature of transitional eras in their anthology. Since Gubar was previously interested in 19th-century female authors, her list featured writers such as Mary Shelley, George Eliot, the Brontë sisters, Florence Nightingale, Louisa May Alcott, and others. Many of these authors are part of school curricula and consequently influence the formation of the image of women in adolescent minds.

Their work received deserved recognition. The anthology edited by Gubar and Gilbert has become an integral part of women’s literature courses. In this work, as in their previous ones, Gubar and Gilbert tried to find a connection and understand whether the male perspective on female authors had harmed female writers. They aimed to explore whether the stereotypes created by men had influenced women’s self-definition.

Racial Issue

In addition to the specific place of women, their roles and all the clichés ever created in the literature regarding women, Gubar examined “woman-centeredness” through the lens of the racial issue. She wrote the scholarly works Racechange and Critical Condition. In these works, she delved into the theme of interracial art and identified the problems within them that created conflicts between the artistic works of authors from different racial backgrounds. In these scholarly works, she evaluated not only artistic creations but also public performances, analyzed social situations and assessed how one race concealed itself behind the behavior of another. Such disguise could be observed in literature when an author writes about the life of another (non-own) race or when white individuals copy the behavior of people of color, for instance. Gubar called this a behavior of racial mockery or envy. It is a silent acknowledgment that one race has things that the other race lacks.

In the 21st century, the noise of the feminist movement began to diminish. From everywhere, Gubar heard that feminism was outdated and not fashionable. However, she did not share these sentiments. On the contrary, she encouraged everyone to revisit the fundamentals of feminism.

Throughout all her research and work, she received accolades from the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Guggenheim Foundation. As a fellow at Princeton University, she authored the book Poetry After Auschwitz: Remembering What One Never Knew.

In 2008, Susan Gubar fell ill with cancer and had to leave her job. She left behind a multitude of works that have become some of the most significant contributions to the world of feminist literature and scholarly research in this field.